Differentiating a quantity with respect to some parameter is a basic component of any simulation. The mathematical definition of this operation, which relies on taking a limit is straightforward. But this definition falls short in three essential ways.

Firstly, in order to be useful for simulation purposes, the definition needs a concrete implementation on a computer. In moving from a mathematical definition to algorithmic implementation, we necessarily must choose a form of discretization and thereby introduce errors - either algorithmic or floating-point rounding errors. We also have to consider performance so we can perform these calculations in a reasonable amount of time. Often this leads to a tradeoff between precision and performance.

Secondly, the definition works on scalar values. Of course, there are other definitions such a directional derivatives along a vector. But all of these definitions have a major shortfall in common. They yield different results in different coordinate systems. Take for example, the gradient of a scalar. It is a directional derivative that yields a vector which points in the direction of the steepest increase and the length of the vector represents the size of the increase. But the directional derivative is defined in terms of some unit-vectors, i and j, which in turn only exists in the context of some coordinate system, S. Hence the directional derivative is represented by some vector in S. But if you choose another coordinate system, S', then the directional derivative yields a different vector. Or more precisely, the components of the vector is different between, S and S', even though they are supposed to represent the same physical, unchanging and coordinate-independent vector quantity.

Lastly, we may think about algorithmic support for partitioning our problem domain so that we can run some form of divide and conquer strategy and compute our results on parallel processes. This requires some design choices that allows for partial calculation of derivatives and an interface that allows for combining partial results in order to continue calculation.

In order to address the first issue, we will implement Automatic Adjoint Differentiation (ADD). This method addresses the computational problem by breaking any given mathematical expression into its basic mathematical operations, say +, -, /, *, ln(x), sqrt, e^(x), cos(x), sin(x) etc. This yields the original expression in the form of an abstract syntax tree (AST). For each of these basic operations, the derivative is known analytically and so there will be no errors introduced due to algorithmic approximation. Then the result of each operation is calculated along with its (analytical) derivative. Finally, each derivative is combined by virtue of the chain rule of calculus and the derivative rules i.e. the sum-rule, product-rule, quotient-rule, etc. and propagated through the AST to yield the derivative of the original expression along with the derivative of each sub-expression along the way. This process works in forward mode or reverse mode. When done in reverse mode, we are technically not calculating and propagating derivatives but the related concept called adjoints. Adjoints can be thought of as dual to derivatives in the same sense one-forms are dual concepts to vectors. As suggested by the project title, we are aiming for the reserve mode, because it has better performance characteristics. This is because this algorithm traverses the AST only once to evaluate the function and once to calculate the derivative with respect to each of the parameters - this is irrespective of the number of parameters with which we need to differentiate. The forward mode has to traverse the AST once for each parameter. In terms of time complexity, we say that the forward mode of automatic differentiation runs in O(n), where n is the number of parameters with which we have to take the derivative. The reverse mode of automatic differentiation runs in time complexity O(1) - constant time. There are many alternatives to AAD. For example, finite differences and variations of it such as forward, backward and centered difference. All of these methods are based on Taylor Series expansions of the mathematical definition and ultimately, the Taylor series is cut off at some point yielding an inherent algorithmic error. For this reason, we do not consider these methods any further.

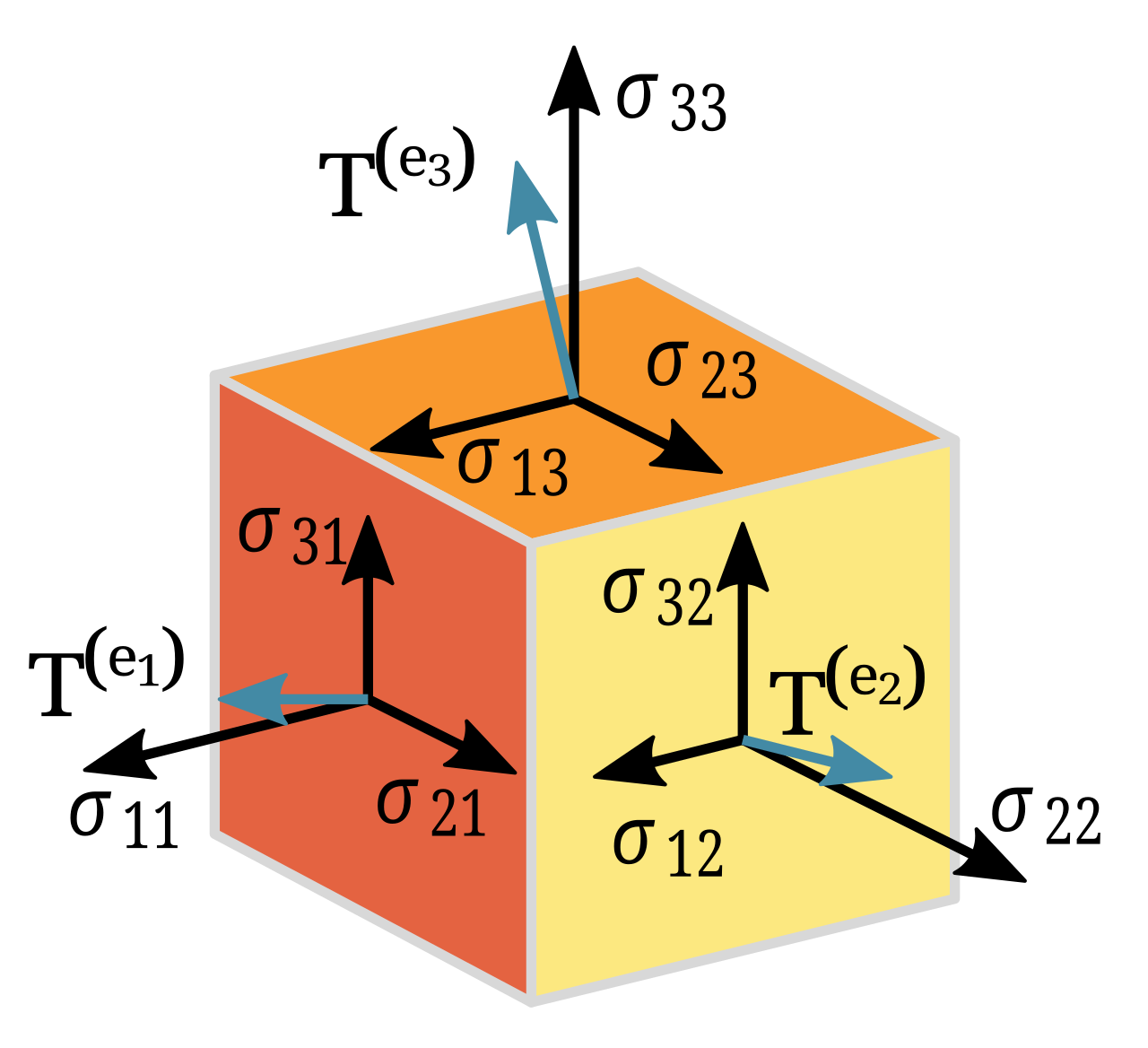

To address the second issue, we need to replace vectors as the fundamental object upon which we take derivatives. Instead we should move on to a concept of combining vectors with dual vectors to yield objects that are invariant under coordinate transformation and therefore coordinate-independent. Consequently, expressions based solely on these types of objects yield the same result in all coordinate systems. Vectors have a single direction and dual vectors have a similar definition in terms of surfaces. Tensors are a generalization of these types of objects and Tensors have a rank to signify the extend of generalization and the notation for Tensors include a set of indices that indicate their rank. There are both superscript indices and subscript indices that indicate the extend of vector and dual vector generalization respectively. Tensors of rank (0, 0) are scalars., Tensors of Rank (1,0) are Vectors, Tensors of Rank (0,1) are One-forms while Tensors of rank (m, n) are general Tensors. More importantly, Tensors are invariant under coordinate transformation. Hence pure Tensor expressions yield the same result in all coordinate systems. Tensors are associated with a number of operations which can be used to build expressions. The derivative of these operations are known analytically, and therefore AAD can be implemented in a version that takes the derivative of general Tensor expressions.

To address the third issue, we will build the code with scalability being a top-of-mind design criteria rather than an afterthought. We will implement a partitioning strategy that allows for the calculation of sub expressions and an interface with which pre-calculated sub expressions can be injected and combined with other pre-calculated sub expressions.

In summary, this project aims to implement a version of AAD that operates on general Tensors of rank (m, n) and allows for partitioning. This implementation will serve as a foundation for further projects. In particular, it will serve as a useful abstraction for implementing scalable Partial Derivative Solvers on Tensor expressions.

The software for this project is MIT licensed and freely available on GitHub at the following location:

Automatic Adjoint Differentiation - software. The code is associated with a GitHub-project which details a roadmap and future development. The project is located here:

Automatic Adjoint Differentiation - project

Sources and Further Reading:

The explanation above is necessarily brief and high-level. A full explanation would take several books and indeed there are plenty good books on these subjects.

A particularly good book on Automatic Differentiation is "Evaluating Derivatives: Principles and Techniques of Algorithmic Differentiation" by Andreas Griewank and Andrea Walther.

A good introduction to Tensors is "A Student's Guide to Vectors and Tensors" by Daniel Fleisch. It will help clarify exactly in what sense Tensors are coordinate-independent objects.

More advanced Tensor concepts are covered in "Introduction to tensor analysis and the calculus of moving surfaces" by Pavel Grinfeld. Pavel is an incredibly clear writer and teacher and it is obvious that he has a deep understanding of the subject matter. He is also able resist the temptation to introduce unnecessary formalism making this book a breeze to read.

We are designing numerical solvers for partial differential equations (PDEs). The PDE solvers are designed to employ mesh-free methods to operate on coordinate-independent Tensors. They are also designed to make use of the AAD implementation on general Tensors to solve Tensor equations. The solvers will take full advantage of the fact that the AAD implementation supports partitioning by allowing for distributed calculations. It will support calculations that run both concurrently and in parallel. Concurrently, through async operations and in parallel by employing multi-threading. We also aim to provide support for fully distributed calculations across clusters of separate compute nodes using a network messaging protocol. Of course each compute node will itself be both async and multithreaded. This will allow us to simulate complex changing geometries such as those appearing in Einsteins Field equations in reasonable amounts of time.

While implementing PDE solvers is not exactly groundbreaking, in many implementations, scaling is an afterthought. In contrast, our PDE algorithms have built-in support for partitioning and our system architecture has built-in support for divide and conquer algorithms. These aspects combined enable us to run computationally scalable simulations on a suitable distributed compute environment. This will be taken fully advantage of in a separate project which aims to build a scalable compute platform based on commodity hardware.

We operate in the intersection between high performance computing and scientific computing. This project focuses on developing the software required to run simulations and perform large scale scientific computations and it will take full advantage of the distributed design of our PDE solvers as well as the support for partitioning in our AAD implementation. The output of this project is a software platform for distributed high performance computing and software strategies for partitioning large scale scientific computations.

Our distributed computing platform is designed to run on commodity hardware. It consists of compute nodes that run on each machine, an orchestration mechanism that is used to orchestrate the distribution of computation for a given simulation, and an administrative module that is used to configure clusters of nodes.

Our focus on commodity hardware is deliberate. It allows us to scale using readily available hardware rather than relying on specialized supercomputers. This not only reduces costs but also democratizes access to high-performance computing resources. This is in line with our philosophy to empower anyone to contribute to our shared efforts.

We have plenty more projects in the pipeline. In particular, we have some really interesting simulation use-cases that we can't wait to share with you.

The laws of physics do not depend on the coordinate system in which you choose to represent them. Therefore, any mathematical expression that we use to represent relationships in physics should also be independent of the choice of coordinate system.

Tensors are independent of the choice of coordinate system. That is not to say that there is no coordinate system, only that Tensors are invariant under change of coordinate systems. Consequently, Tensors evaluate to the same result in all coordinate systems.

This is an extremely desirable property when working with scientific relationships and therefore, expressing relationships using Tensors is often the most natural way to express scientific relationships. Indeed, one of the central goals of Tensor calculus is to construct expressions that evaluate to the same result in all coordinate systems.

Many standard expressions in mathematics are expressed in forms that depend on the choice of coordinate system. For example, the gradient of a scalar function is often expressed using partial derivatives with respect to the coordinates. Therefore, this expression is not coordinate-independent and will change if the coordinate system is changed. But the gradient can be expressed as a Tensor operation in which case it will become coordinate-independent and will yield the same result regardless of the choice of coordinate system.

There are many good reasons for wanting to switch coordinate systems. For one, some coordinate systems are better suited for certain types of problems. For example, spherical coordinates are often used when dealing with problems that have spherical symmetry.

But more fundamentally, some expressions such as Einsteins Field equations describe relationships where the geometry itself is dynamic and changing. In such cases, there is no single coordinate system that can be used to express the relationships. Instead, the coordinate system must change along with the geometry. And then expressing relationships using Tensors is not just a convenience, it is a necessity.

Even when you are not directly working with changing geometries, expressing relationships using Tensors can greatly simplify the expressions. For example, Maxwells equations of electromagnetism can be expressed as a single Tensor equation in covariant form. This is much more concise and elegant than expressing the equations using the traditional vector calculus form which consists of four separate equations.

As a final motivation, consider the situation when you want to simulate Maxwells equations in or through gravitational fields in which case Tensors also become a necessity.

We aim to build state-of-the-art numerical methods to solve systems of equations and simulate dynamic aspects of those systems - accurately and in sufficient detail to achieve our ambitions. We are driven by the conviction that through rigorous scientific methodology, engineering excellence, and unwavering dedication, we can solve problems previously deemed intractable. We embrace challenges that push the boundaries of what is known, and commit to the long-term vision required to achieve transformative breakthroughs.

We recognize the contributions of the scientific community throughout history and the hard work of the open source community. We make use of scientific contributions while we derive our solutions from first principles. We use software from license compatible sources, while recognizing that detailed and accurate simulations are paramount to our efforts, and engineering of our own software stack from the ground up, is necessary for the ambitions we aim to achieve.

Curiosity is the most fundamental driver of scientific progress and a bedrock of our civilization. We are engineers at our core, and we are focused on solving problems as opposed to selling products and services or dealing in political messaging. Science is a human endeavor, and it should be free and accessible to anyone. Anyone who wants to contribute to our common pursuit should be empowered to do so.

We rely solely on free and open source software and tools in order to always maintain control over our processes and reduce exposure to potential attempts at coercion and economic or political pressure. This will help guarantee that our decisions are always driven by our ambitions and goals and unaffected by outside influence.

Science and engineering are not value-neutral endeavors. We are deeply committed to ensuring that our work serves the needs of humanity and advances our collective flourishing. We recognize our responsibility to think critically about the broader impact of our innovations, to consider potential misuse, and to advocate for their principled application. Our commitment to ethical responsibility means we will always prioritize human welfare, dignity, and freedom over profit or political convenience.

We believe that privacy is a fundamental right and that individuals should maintain control over their own data. We are committed to transparency in our data practices and will never sell, share, or exploit personal information. Your data is yours to own, and we support your right to access, modify, and delete information you share with us at any time.

GNU/Linux is a popular free and open source operating system. We build on software from GNU and the Free Software Foundation and use Linux from the Debian family of distributions. This enables us to have full control of all aspects of the operating system and without binding ourselves to any particular commercial or political interests. We care about transparency and privacy and believe in the spread of free software as a tool to help facilitate these principles.

The Linux Kernel is owned by the Linux Foundation and the Linux Kernel is licensed under the GNU General Public License version 2. Many of the fundamental tools associated with GNU/Linux is maintained by the Free Software Foundation and are licensed under the GNU General Public License version 3. The Debian GNU/Linux distribution is managed by the Debian project. Debian is licensed in a manner consistent with the Debian Free Software Guidelines.

We are programming language agnostic and view programming languages as mere tools. But for practical reasons, we must focus on a set of tools and technologies which fit our philosophy and which can be used to create solutions to solve the types of problems we are aiming to solve.

The primary programming language for these efforts is Rust. This is because Rust is focused on high performance while providing advanced abstractions at minimal cost, as well as relative safety through a novel borrow-checker and enforcement of the RAII pattern across scares resources. It also provides excellent support for the functional style of programming which, in turn, lends itself well to scientific computations.

The Rust project is owned by the Rust Foundation, a nonprofit organization established to support the Rust programming language and its ecosystem, and the Rust compiler and standard library is dual licensed through the MIT and Apache 2.0 licenses making Rust highly license compatible and in line with our philosophy.